The 2019 Jokulhlaup: Alaska Whitewater During a Glacial Flood

As whitewater boaters in Wrangell St. Elias National Park, our work is dictated by the powerful geologic forces at work.

In general, geology is a slow force that shapes the earth over thousands or millions of years. But every once in a while, the earth conspires to alter a landscape in a sudden, cataclysmic event. Earthquakes, floods, and volcanoes are all examples of the abrupt, sometimes violent nature of the earth.

Meet the jokulhlaup. Pronounced “yo-kull-hop”, this Icelandic word literally means “glacier run” and describes a sudden breach of a glacial dam, causing water from a lake to drain suddenly into the surrounding valley. Jokulhlaups have been happening for hundreds of thousands of years in Alaska, causing catastrophic, mega-floods at the end of each glacial period. In fact, during the last glacial period much of what is now Wrangell St. Elias National Park was under a massive lake that produced the largest known jokulhlaups in the world, with an estimated peak discharge of 2 million cubic feet per second. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. I’m going to tell you about a jokulhlaup that is in comparison tiny, but has a huge impact on the McCarthy-Kennicott Valley.

Hidden Lake looking east, full, a week before the 2018 jokulhlaup. Photo: Elvie Underwood

It all starts in Hidden Valley, a lovely little spot just to the west of the Kennicott Glacier, about 11 miles north of McCarthy. Hidden Creek flows through the valley, but instead of flowing under the glacier as many creeks do, the water pools up at the glacier’s edge, forming Hidden Lake. As the summer progresses and snow in the surrounding mountains melt, the lake grows and grows but that water has no outlet.

Then one day in July, the lake drains.

Throughout the summer it has amassed so much hydraulic pressure that it is able to actually lift the glacier that has been trapping it and all that water flows in channels under the glacier.

Hidden Lake looking west, empty, just hours after the 2019 jokulhlaup. Photo: Caitlyn Tetterton

Eventually, the water makes it to the Kennicott Lake at the terminus of the glacier. It raises the level of the lake by inches, jostles around some icebergs, and finally finds it’s ultimate goal- down the Kennicott River on its way to the sea.

What does this mean for boaters like us who spend almost every day on the river? How do we cope with a cataclysmic flood that alters the entire landscape of the river we run? Every year the jokulhlaup is different, and we always take care to assess the changes of the river and reschedule trips if necessary. But in the first 24 hour period after Hidden Lake breaks, we react in typical McCarthy fashion- we celebrate.

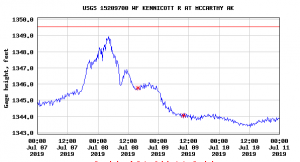

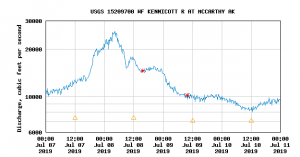

On the morning of July 7, 2019, the gauge that measures the flow of the Kennicott River showed a slight but steady increase from a normal flow of 10,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) to 13,000 cfs. The past week had been one of the hottest on record for the valley- some thermometers reading 90 degrees in the sun- so the increase wasn’t necessarily surprising. Then, around 4 pm, a pilot flying over Hidden Valley broke the news- Hidden Lake had drained! Between 4pm and 10pm, the water rose nearly 3 feet and reached a flow of 20,000 cfs.

The gauge at the footbridge measuring cubic feet of water per second during the 2019 jokulhlaup. Photo: USGS

The gauge reading height of the river during the jokulhlaup. Photo: USGS

High water on any river can pose a risk to boaters, but the jokulhlaup presents unique conditions that make it a playground for the experienced and safe paddler. Unlike regular floods due to rain, the glacial flood does not wash out any trees that could create dangerous obstacles to boaters. The occasional iceberg does roll down the river, but ice behaves like a rock and is easily avoidable. The rapids swell, creating powerful and fun whitewater to paddle on. When the gauge read 20,000 cfs, the McCarthy River Tours crew assembled and pumped up a couple of boats.

It was time to raft the jokulhlaup.

Residents of McCarthy and Kennicott spend every jokulhlaup together in the same place- the Kennicott River footbridge. Because you never know when exactly the flood will happen, it’s always a surprise party for everyone involved to celebrate the dynamic nature of this place and to watch paddlers ride the waves. From the bridge, you can see the banks of the river erode and listen to massive boulders rolling beneath the water, crashing like thunder. As the first kayaker paddled beneath the bridge, the crowd cheered wildly. Several more packrafts and kayaks followed, splashing through waves with massive grins on their faces.

The crowd on the footbridge helped to launch professional whitewater kayaker Brendan Wells into the river below.

Our 6 guides put in their two boats at the lake and paddled into the river. The waves were huge and rolling- the river was almost unrecognizable at this level. Laughing and cheering, they hit every rapid head on, rejoicing in the freezing water that splashed them in the face. They found a calm eddy several yards downstream from the footbridge and carried the boats back up to run it again, and again, and again. Even as the sun set, the river grew, and boaters reveled in the huge water and cheers from their fans ashore.

Boating in the Wrangells is usually a peaceful, solitary affair. The jokulhlaup is the one occasion where you boat with a rapt, enthusiastic audience.

The MRTO crew enters the first rapid of the river while icebergs loom in the lake behind them. Photo: Paul Scannell

MRTO Guides Amanda, Sam and Sid encounter a giant wave on the Kennicott River during the 2019 jokulhlaup. Photo: Paul Scannell

After one last run under the bridge, the guides headed home via the river, discovering huge water around every turn. At the takeout, they found parts of our riverside property had flooded- picnic tables and benches were floating in a lake of cold, silty water at the rivers edge. But just as suddenly as the water rose, the next day it dropped. By July 9th it had returned to a normal flow of 10,000 cfs after peaking at 24,000 during the night. In the next days, our guides paddled the river numerous times to familiarize themselves with the changes that occurred during the flood, making sure it was safe to bring guests down. Banks have eroded, new channels have opened up, old familiar rapids bear new names and faces, but the Kennicott is back to it’s same fun, splashy Class III self.

Huge thanks to Paul Scannell for the incredible photos. His work can be found on Facebook and Instagram @paulscannellphotography and http://www.paulscannellphotography.co.uk/